What is an Annotated Bibliography?

Sometimes researchers want to know more about the context of a source, and why the writer has chosen to focus on it in their work. That’s where annotated bibliographies come in.

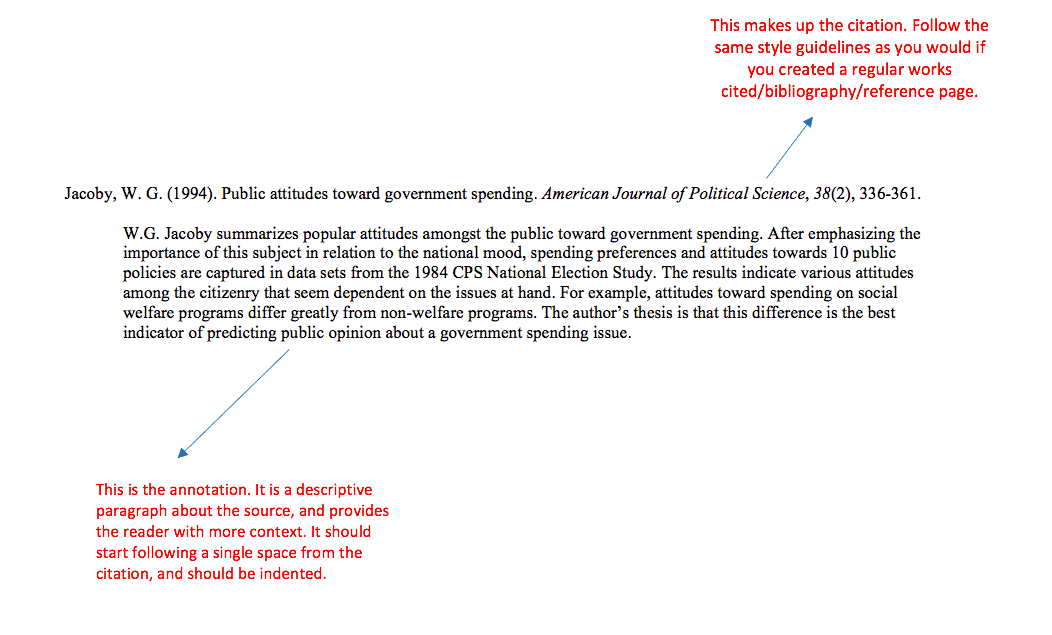

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, documents, etc. Normally, a works cited page or reference list simply displays each source via a citation. However, in an annotated bibliography, each citation is followed by a brief descriptive and evaluative paragraph. This paragraph is known as the “annotation,” and is usually only about 100-150 words long.

The purpose of an annotated bibliography is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, location, and quality of the sources that are cited in the paper or work. You should always check with your teacher or professor first to see if an annotated bibliography/works cited page is needed for your paper.

Has your teacher asked you to write an annotated bibliography for your paper? Don’t know how to get started? Check out the example below for some quick tips on how to structure an annotated bibliography.

The following example uses APA format (Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th edition, 2010) for a journal citation. While the format for the citation itself would change if you used a different style, such as MLA format, the format of the annotation itself would remain the same:

...

What is a Bibliography?

Whenever you quote, paraphrase, or take notes on someone else’s work, you should keep track of the sources the information came from. This will help you avoid plagiarism when you begin writing.

You can keep track of your sources in a few different ways:

- Place the author’s name in parentheses after quoted or paraphrased text.

- Organize your notes under headings with the source information.

- If using note cards to keep track of information, write the source of the information on the back of each card.

What is a Bibliography?

Let’s begin with a brief definition. A bibliography is a list of sources that an author used to write their piece. It is usually included at the end of a project or paper, and includes information about each source like the title, author, publication date, and website if the source is digital. Each set of source information is called a citation.

For example, here is a website citation in MLA format:

Joyce, Christopher. “Plastic Is Everywhere And Recycling Isn't The End Of It.” NPR, 19 July 2017, www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/19/538166682/plastic-is-everywhere-and-recycling-isnt-the-end-of-it.

A bibliography usually has several citations. Here is an example of a bibliography (unformatted):Works Cited

Azzarello, Marie Y., and Edward S. Van Vleet. “Marine Birds and Plastic Pollution.” Marine Ecology Progress Series, vol. 37, no. 2/3, 1987, pp. 295–303. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24824704.

Hall, Eleanor J. Recycling. KidHaven, 2005.

Hopewell, Jefferson, et al. “Plastics Recycling: Challenges and Opportunities.” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, vol. 364, no. 1526, 2009, pp. 2115–2126. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40485985.

“How Much Plastic is in the Ocean?” It’s Okay to Be Smart. YouTube, 28 Mar. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YFZS3Vh4lfI.

Joyce, Christopher. "Plastic Is Everywhere And Recycling Isn't The End Of It." NPR. 19 July 2017, www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/19/538166682/plastic-is-everywhere-and-recycling-isnt-the-end-of-it.

Manrich, Sati, and AmeÌlia S. F. Santos. Plastic Recycling. Nova Science Publishers, 2009.

Why Have a Bibliography?

There are many benefits to creating a bibliography. Listen to the sound clip below: http://fast.wistia.net/embed/iframe/ara4ebv511

In summary, bibliographies serve many purposes:

- They help you keep track of your own research.

- They can help your readers find more information on the topic.

- They prove that the information in your research came from trustworthy sources.

- They give credit to the original sources and authors. It is a central location for all of your citations.

How Do I Create a Bibliography?

What your bibliography looks like will depend on a few different things, including what information you want/need to keep track of and what citation style you are using.

There are several different citation styles. Each requires slightly different information and formatting. The most popular styles used are MLA format and APA format. You can follow a citation guide, use a citation generator like BibMe, or see your teacher to help you structure your bibliography.

There are also plagiarism checker services that can assist you with identifying text that may need a citation, and then helping you create citations.

...

What Makes a Good Essay?

Over the course of your studies, you have probably been asked to write an essay. So what exactly is an essay? What are its components? How do you write a good one? Read on for some helpful tips!

What is an Essay?

Generally, an essay is a written piece that presents an argument or the unique point of view of the author. They can be either “formal” or “informal.” “Formal” refers to essays that are done for a scholarly or professional purpose.

“Informal” essays, conversely, express personal tastes and interests, and can have an unconventional writing structure. Essays are meant to provide a platform for writers to express their ideas within a specific type of format.

What are the Different Types of Essays?

There are many different types of essays, each with their own individual purpose and method of presenting information to the reader. Here are the most common:

1. Narrative: Usually written about a personal experience, these tell a story to the reader.

2. Argumentative: Requires research on a topic, collection of evidence, and establishing a clear position based on that evidence.

3. Descriptive: The writer must describe an object, person, place, experience, emotion, etc., and is usually granted some stylistic freedom.

4. Expository: Often in a “compare and contrast” format, this also requires an original thesis statement and paragraphs that link back to a central idea.

What Makes a Good Essay?

To construct a well-formed essay, you need to include several different key components. These are vital to ensuring that the reader is convinced of your argument, hooked on your story, or adequately informed on your topic.

Almost all essays should be broken into four parts: Intro, Body, Conclusion, and Citations. Within these four parts, be sure to include the following components:

Introduction

Your introductory paragraph should serve to frame the rest of your paper in the reader’s mind. Think of it like a preview; you want them to move forward from here with a clear understanding of what the central idea of your paper is.

In order to frame the central idea, many essays contain a thesis statement, which is a one or two sentence phrase that captures the theme of the paper. These should be as specific as possible, and should be included as the last part of your intro paragraph.

Example thesis statement:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.Body

The body of your essay is where your evidence is presented and/or your point of view is made clear to the reader. Each body paragraph should further the central theme you put forth in your thesis statement.

The body paragraphs should each include a topic sentence that drives the rest of the paragraph, and relates back to the thesis statement. Be sure to include transition sentences between paragraphs to ensure a nice flow to your writing.

Within each paragraph on a specific idea, present any outside evidence that you have used to formulate your idea. Here is where you should be sure to include any necessary in-text citations, whether they be in MLA format, APA format, etc.

Conclusion

Your conclusion paragraph should neatly wrap up all of your ideas and evidence, calling the reader back to your original thesis statement. A good way to conclude your writing is to restate your thesis statement or central idea in a different way, making sure to include the main points you made in your paper.

If you are having trouble formulating your essay’s conclusion, read through your paper and then say to yourself “So what?” This helps to summarize the main idea of your paper in your mind.

Make sure that your reader is left with an impression or something to think about in relation to your topic. This is a hallmark of an effective essay. This is most important in argumentative essays.

Citations

Depending on what citation format your teacher prefers (MLA format, APA format, etc.), you should include a reference list at the end of your essay, which lists the outside sources where you attained information while creating your paper.

The citations in your reference list should include any sources that you have referenced within the body of your essay using in-text or parenthetical citations.

For help with creating citations, check out the citation guides on BibMe here http://www.bibme.org/citation-guide.

Finally, always remember to proofread your essay before handing it in to your teacher!

Four Steps for STEM Majors to Rock that Next Paper

STEM students everywhere feel the pain of writing assignments. As people who would rather spend their time working with numbers and figures, sitting down to write a paper can seem so tedious and boring. But effective communication is one of the most important skills we can learn in college, as it’ll help us stand out when we express ourselves. STEM students with writing abilities are super valuable!

Even if you are only required to take one writing class, it’s important that you use this opportunity to enhance your skills and build confidence in your own writing. With online tools like the BibMe Plus grammar and plagiarism tool, writing becomes much less intimidating.

While you’re working on your writing, approach the assignment like any other math problem you would tackle. You can work out your writing using four steps: identify the problem, show your work, cut out unnecessary steps, and check your final answer.

1. Identify the problem

The most crucial part of your paper is your argument or the problem to be considered. When thinking through your thesis, go through and review several, peer-reviewed sources. Academic sources can be scary, but they contain the research you need to make your points.

After you’ve done research, craft your thesis statement to capture the essence of the problem. One trick is to rephrase the assignment as a question and then make sure your thesis answers that question. Clearly identify the problem or discussion that is of interest and communicate that you understand the problem from all angles.

Writing your paper will be so much more exciting if you can find a topic that interests you, too. You might even be able to find a subject that relates to science or math in some way.

2. Show your work

Showing your work means that you provide clear and reasoned evidence as to how you are developing your argument while incorporating outside information. This evidence should come from outside sources and try to show various views of an argument.

This will make the stated claims clear and your writing easy to understand. Clearly point your reader in the correct direction, using logical steps that follow one another.

Also important: cite your sources so others can confirm or read more on the evidence you’ve used. If you don’t know which citation style to use, ask your professor. Commonly used citation styles include MLA format, APA format, and Chicago Manual of Style.

3. Cut out unnecessary steps

It’s tempting but don’t try to impress your teacher by using the biggest words or the longest, most complicated sentences you can think of. This will make the paper hard to follow. Simple and clear is always better, just like when solving an equation.

Even if you have a gigantic assignment, you still have to cut out the fluff. This means actively checking for lengthy or wordy sentences and avoiding passive voice. For example, instead of:

The cake was baked by Mary.

You’d write:

Mary baked the cake.

Writing assignments in college require active voice, which can be a tough transition from the lab reports that require passive constructions. After you’ve written your draft, read it aloud. Listen for passive voice, and circle any words that you’re not quite sure about. After that, cut out any words that are unnecessary and revise until your writing is as clear as you can make it.

4. Check your final answer

Any time you solve a math problem, it is a good idea to check your work to make sure that your answer makes sense. Writing is no different!

Nailing a smooth flow and good writing transitions on the first try can be tough. Try making a flowchart with one-word descriptors of each paragraph, and rearrange them until you find the order that makes the most sense if your organization doesn’t seem right. Your topic sentences should serve as your roadmap, so ensure that these follow each other logically. Reviewing the flow of your argument is always a great last step in writing!

Being a mathematician or a scientist means that you will have to explain your work to the world, and mastering writing is the key to spreading your ideas and your accomplishments. The good thing is that there’s likely no need to drastically change or enhance your writing. Approaching your assignments like any STEM exercise is a great way to make you feel more at ease. And don’t be afraid to ask for help, whether that be from your TA, a tutor, or your campus writing center. Just take the assignment one step at a time.

Trying to remember how linking verbs work? Need a refresher on what is a prepositional phrase? Looking for an interjection to use in your next paper? Check out our BibMe grammar guides for help with the above and more!

...

6 College Tips for Freshmen

So you’ve applied, been accepted, and now it’s time to go. However, gone are the days of your high school guidance counselor choosing your classes. To help make the transition a bit more smooth, we’ve included 6 tips.

Schedule an Advising Appointment

Your collegiate Academic Advisor is a tremendously useful resource for your years in university life. They are there to be a resource for you in all aspects of life, from academics to personal crisis. Therefore, it’s important that you take some time to meet with them on your registration day. They will likely ask some questions about your ambitions, what type of student you want to be while at college, and the usual “getting to know you” type of drill. Take all of these questions seriously, as they will really help your advisor to steer you in the right direction.

Take Time to Look Around Housing

Your dorm room will soon be your home away from home. In order to get an idea of what dorm life is like, ask to see a demo room in one of your school’s housing complexes. Consider taking a tape measurer with you to get an idea of layout and furniture and take some pictures to share with your roommate.

Get Your Student ID

School may not start for another few months, but that does not mean you can’t start taking advantage of student discounts! Most universities load your information into their ID database in the few weeks after you accept your offer. Consult your school’s ID center for specific information and requirements, but generally a government issued photo ID is all you’ll need to get your card. As an added benefit, by getting your card early, you’ll save yourself lots of time since you won’t have to wait in line during the first few days of classes.

Eat in the Dining Halls

Even if your school is not picking up the tab, your registration day can be a great way to get a feel for your school’s dining centers. Almost all universities offer day passes which you can purchase at the door.

Leave Mom and Dad Behind

Today is your day. For the first time in your life, you get to set the tone for your year. Let your parents go to meetings designated for them and start getting some practice in adulting by attending the other meetings on your own. They are only a text away with any questions that come up, and you will see them again in a few short hours.

Come in With a Plan

Part of being an adult is picking and then sticking with a plan. Have an idea of what types of classes you might want to take, a plan for General Education requirements, and a set of goals for the upcoming year.

Best of luck to you as you start your collegiate journey!

Writing Tip: BibMe can help you easily cite your sources in MLA format, APA format, and more!

...

What is a Paraphrase?

One of the goals of a research project is to defend your argument or claim by using other sources as evidence. We do this when we argue or engage in a discussion with our friends; we backup our claims by including evidence from other sources, perhaps by sharing information from an article we’ve read or a show we’ve watched.

When creating a research project, we backup our claims in the same way. We either include exact lines of text or we paraphrase the information from other sources. This page focuses on how to effectively paraphrase information from other sources.

Before we get started, what is paraphrasing? Paraphrasing is the act of using another person’s information in your own project, but rewording it in a way that uses your own words and writing style.

Why Paraphrase?

Quotes are useful and great to use in a paper, but not as the sole content of the paper. Imagine filling a paper with nothing but quotes related to your topic. It’d be easy to do, but the paper would not include any of your own thoughts and your teacher may view the paper as lazy and not well written. On the other hand, with a paraphrase you put the information into your own words. This demonstrates that you’ve understood and critically considered information. In addition, it’s an opportunity for you to demonstrate your own thoughts on the topic.

Paraphrasing is also a useful way to concisely summarize information. Perhaps you loved a long passage but you don’t want to quote the entire thing in your paper. Solution: simply paraphrase it!

What it Looks Like

Let’s look at a direct quote, or exact line of text, from the famous children’s book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, by Roald Dahl:

Walking to school in the mornings, Charlie could see great slabs of chocolate piled up high in the shop windows, and he would stop and stare and press his nose against the glass, his mouth watering like mad. Many times a day, he would see other children taking creamy candy bars out of their pockets and munching them greedily, and that, of course, was pure torture (Dahl 8).To paraphrase this properly, we need to reword it in a different way, using our own style of writing, while capturing the same meaning and essence of the movie quote.

Here’s an acceptable paraphrase for the paragraph from the book:

Poor Charlie would suffer as he watched his classmates enjoying chocolate bars and as he passed the candy store, which was fully stocked with delicious treats (Dahl 8).In the above example, we’re using the same concept and idea as the book’s text, but writing it in our own words.

What it’s Not

Paraphrasing is tricky because it requires us to read text, analyze it, and write it out in our own words and in our own style.

It is NOT acceptable to simply substitute the words in the text with synonyms.

Here’s an unacceptable paraphrase for the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory passage:

While strolling to class at daybreak, Charlie viewed giant pieces of chocolate stacked in the store’s windows. He would gaze at the chocolate and squeeze his nose to the window pane, drooling like crazy. On numerous occasions during the day, he’d view classmates pulling luscious chocolate bricks from their pockets and enjoy them immensely. It was awful for Charlie (Dahl 8).This paraphrase is too similar to the original quote. It’s considered plagiarism!

How to Paraphrase

Follow these steps to paraphrase text from a source:

- Read the text from the original source and re-read it again to fully comprehend the author’s meaning.

- Put the information to the side and without looking at it, rewrite the information in your own words and in your own style.

- Glance at the original source again to make sure you have included the key concepts in your paraphrase.

- Even though you paraphrased the information in your own words, you still need to show that the information came from another source. You do this by creating an in-text citation and placing it after the paraphrase. You can see the in-text citations in the examples above. They are shown as (Dahl 14). The next section explains how to properly create and format an in-text citation.

How to Cite a Paraphrase

While getting into a heated debate with our friends, it’s always helpful to backup our argument with evidence from other sources, but what we generally do not do is share who the author of those sources are. That’s something that we must do with research projects. Depending on which citation style you choose to format your paper in, such as MLA format, APA format, or one of the hundreds of other styles available on BibMe, you have to include a couple of items about the source, directly after, or close to the paraphrase. This helps the reader understand that the text or information they read is coming from another source.

Here are the most common ways to cite a paraphrase in the body of your work:

MLA:

(Last name of the Author page number).

Example:

Here is my paraphrase (Dahl 8).

APA:

(Last name of the Author, year the source was published).

Example:

Here is my paraphrase (Dahl, 1998).

These in-text citations provide brief information about the source. If a reader wants to find more information about the exact source, they can head to the last page of the project and review the Works Cited list, Reference page, or bibliography. That’s where the reader can find the full citations, which tells more about the source.

Here’s the full citation in MLA:

Dahl, Roald. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Puffin Books, 1998.

Here’s the full citation in APA:

Dahl, R. (1998). Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. London, England: Puffin Books.

...

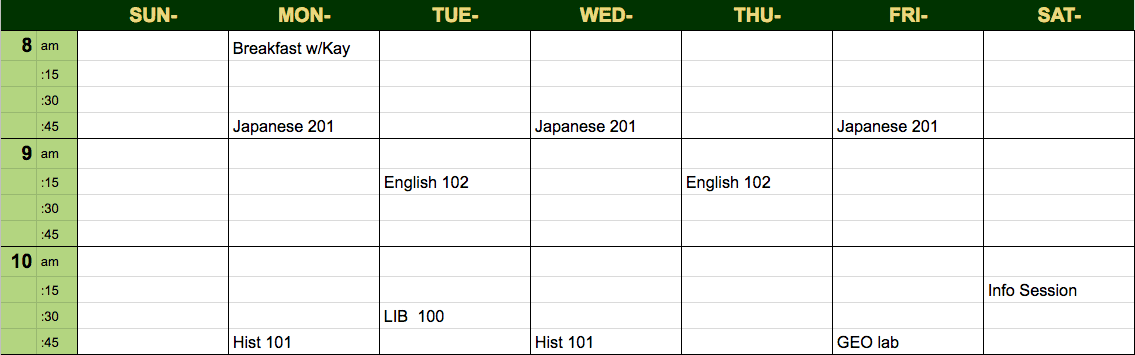

Planning the Perfect College Schedule

Think back to those high school days where you would roll out of bed at 6 am, get to school, and follow the same schedule as everyone else. Now, imagine a place where you can set your own schedule, choose your professors, and establish the routine for the day. Welcome to college! To help you make the perfect college schedule, here are 5 tips to make your routine a good one.

Be Realistic About Your Sleep Schedule

Are you the type of person to wake up bright eyed and bushy tailed, even if it’s 6 a.m.? That may have been the case in high school, but be sure you fully consider the college workload and social atmosphere before choosing to take early classes. Most college students think 10 or 11 am is a “sweet spot” for class starting times, and tend to find they lose focus around 3 p.m.

Schedule Time for Lunch

Nothing is worse than going to back-to-back classes in the middle of the lunch breaks. Do your stomach a favor by scheduling a break of at least 1 hour to eat mid-day. Then, stick to it. As tempting as it may be, try to take this time to relax so that when you return to classes, you can do so with focus.

Don’t Schedule Too Many Classes on One Day

In college, you need to focus not only on class time, but also on homework. On average, expect to spend at least an hour and a half of homework for every hour spent in class. To that end, it really isn’t a good idea to schedule your homework-intensive classes on one day. You will find you become swamped with work on these days, even if you are a person who generally manages your time well.

Count Credit Hours, and Classes

Most, if not all, classes at your institution should have a number of credit hours associated with them. A standard class will generally be around 3 credits, while more intensive classes may be up to 5 credit hours. Light classes are generally offered at 1 or 2 credits. With that in mind, most students schedule approximately 15 credit hours per semester. However, keep in mind that several low-credit classes can be just as intense as a few high-hour classes.

Listen to Your Academic Advisor

Advisors are a godsend when it comes to planning academic work. Before making your schedule final, be sure to sit down with them to make sure that your plan makes sense, will help you accomplish your academic goals, and is reasonable. Be sure to ask any and all questions you have; these people genuinely want to help you be the best student you can be.

With great choice, comes great responsibility. But, with these tips in mind you are well on your way to planning the perfect college schedule.

When you have a paper to write, BibMe can help you cite your sources in MLA format, APA format, and more!

...